Seahawks Head Coach Mike Macdonald Faces A Familiar Problem: Run Defense

A spiraling Seattle Seahawks defense is fresh off consecutive bottom five rushing seasons. Mike Macdonald should be familiar with such an issue: Baltimore's run-stopping similarly collapsed in 2023:

Mike Macdonald—new Seahawks head coach—brings hope that the NFL’s latest hot shot can solve Seattle’s defensive problems. The defense has spiraled over the last three seasons, placing 20th in DVOA in ‘21, 22nd in ‘22, and 28th in ‘23. While Pete Carroll enacted yearly coaching, scheme, and player changes designed to correct the issues, the end product only worsened. Enter Macdonald.

Macdonald coordinated a Baltimore defense that became the first in NFL history to lead the league in sacks, takeaways, and points allowed in 2023. His unit was number #1 ranked in DVOA. And yet, somehow, that Ravens-Macdonald pairing shares a troubling commonality with last year’s Seahawks D: run defense.

2023 Football

In high school history classes I used to stare at a quote from American philosopher George Santayana saying “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Let’s revisit 2023 football with this in mind.

In Weeks 1 to 5, the Seahawks’ defense was seventh in EPA per rush attempt and fifth in points saved per run, according to SIS. Weeks 1 to 8 saw them seventh in points saved per run. And using RBSDM.com to account for garbage time (win percentage of 20/80 filter) Seattle’s run defense was eighth in EPA per play over the first nine games of the season.

Following Seattle’s Week 9 shellacking at the Baltimore Ravens, I asked Pete Carroll whether, rough last outing notwithstanding, the first half of 2023 performance was what the head coach was aiming for when he expressed exactly ninth months prior, on January 16th, a desire for Seattle to be more “dynamic” up front.

“Yup, yeah it is, and the use of our guys, you know in the roles that we’re asking them to fill, is working out well, you know?” Carroll told me October 16th.

In the front they used the majority of the time—a nickel, four-down, over front—the Seahawks adjusted their nose tackle from playing inside the shoulder of the guard (like in 2022) to playing in an outside shade on the center, resulting in more of a one-gap mindset that clarified run fits.

To make this work in 2023, Seattle also came with better complimentary movements and pressures. All of the offseason talk from Carroll about his increased schematic involvement—“jumped back into my work in a way that I haven’t done for a few years…diving in as deep as I can dive”—was visible on-field.

Most crucial of all: the Seahawks’ run defenders played with better execution and cohesion.

“Right now what’s working for us is we’re playing really strictly disciplined football and the guys are connected really well, front guys and gap control stuff that has to take place,” Carroll explained to me of Seattle’s nickel four-down run D.

“You know, to be consistent in the running game, it’s really connected well and that’s, we’ve been able to hold up doing it and we’ve had very consistent run so far this season.”

Of course, the Seahawks’ poor run defense came to be the norm following Week 9. By season’s end, Seattle’s promising run-stopping beginnings were warped into distant memory, where the Seahawks run defense placed bad in the league by basic metrics (sixth-most yards per carry, second-most rushing yards per game) and advanced (third-worst in SIS’ points saved per run play, worst in EPA per rush attempt).

This level of regression is a large reason why Pete Carroll was fired. But how is the past relevant to 2024 Seattle? Well, contrast is useful for building understanding and learning. Like comparing single malt scotches to one another, weighing up similarly flavored defensive strategies provides real learning.

Baltimore

And what do you know? Akin to 2023 Seattle, Macdonald’s Baltimore used nickel four fronts at a high rate, with these designs often asking the nickel defensive back to be involved in the immediate run fit as the seventh defender. A similar performance trend exists for them.

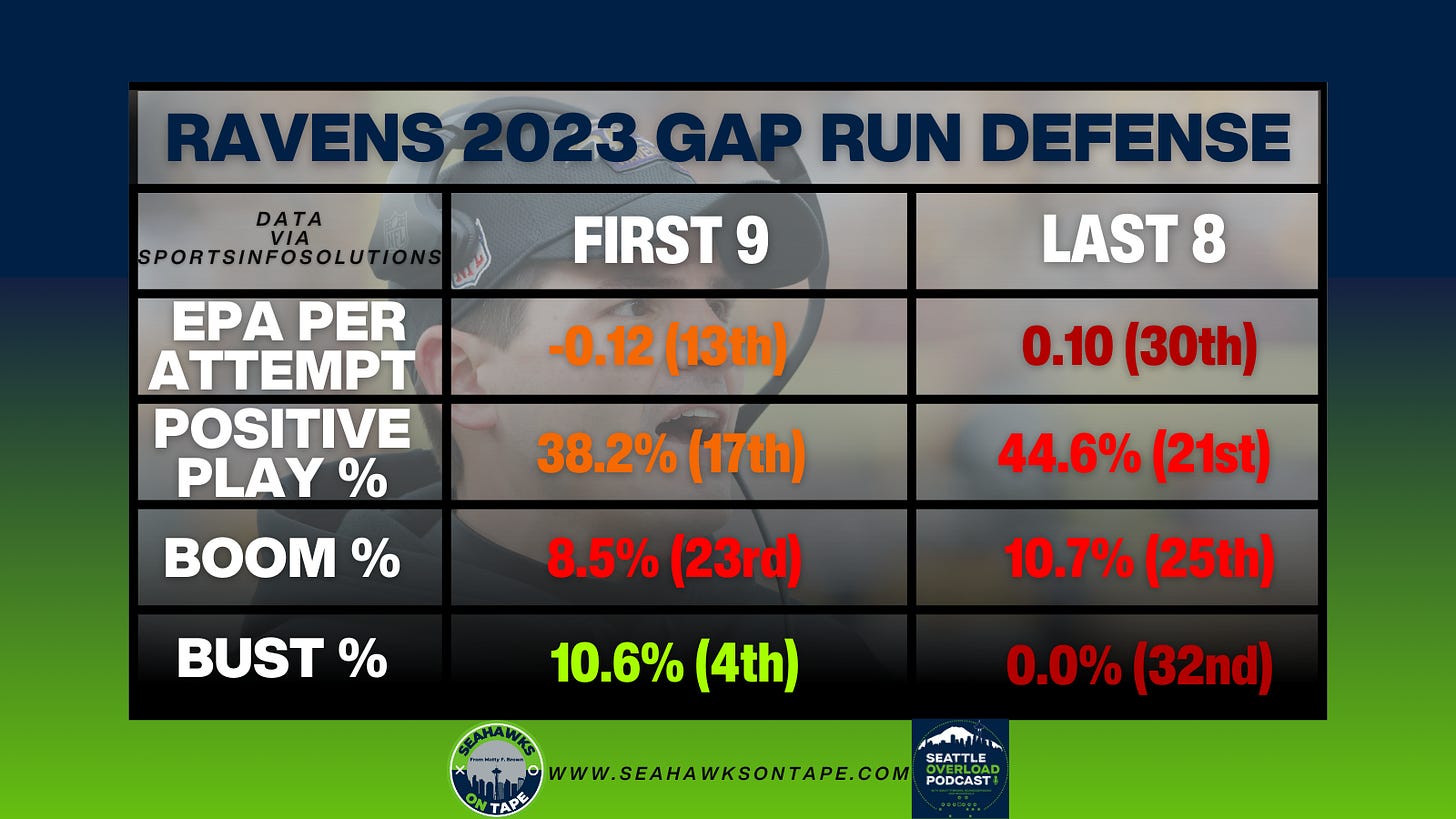

Last season’s Ravens had a quality rushing defense by rushing EPA per play and success rate in the first nine games; then collapsed to being close to league-worst. You might think this was a case of Baltimore being an excellent team and therefore being up big on opponents, resulting in intentionally softer run defense. No: instead, accounting for these game states only sees Baltimore’s run defense worsen.

The Impact

It’s trendy to talk about prioritizing pass defense over run, with some merit, but there is always a point that teams must be able to stop the ground game. Baltimore’s loss in the AFC championship round hosting the Kansas City Chiefs shows this impact.

Yup, even in the match-up where the Ravens’ D registered a second half shutout of KC, their shaky run defense did matter. “[We] had the ball for nine minutes in the first half,” head coach John Harbaugh reflected in Baltimore’s end of season press conference the following Friday. “So those two long drives [by the Chiefs] took us out of the opportunity to call any kind of plays.”

In those first half drives, Kansas City utilized seven gap runs (more on gap later) with a 57.1% positive play percentage, 0.0% bust percentage while averaging 0.20 EPA per attempt.

The complimentary football aspect a defense contributes towards grows very difficult with poor run defense, as the defense stays on the field longer and struggles to get the ball back quickly to their offense. Indeed, Baltimore’s 2023 three-and-out percentage was 22.2%, 25th in the league and lower than the league average rate of 24.3%.

Why did this happen? What can Macdonald learn?

So, getting all Santayana about it, why exactly did this happen last year to Baltimore and Seattle? And how can Macdonald learn from this recent history?

The Seahawks were severely impacted by losing their best run defending outside linebacker, Uchenna Nwosu, to a season-ending pectoral injury suffered in Week 6. Nwosu’s ability to bring dynamic edge play and “take shots” was invaluable. His absence only made his quality more obvious, the knock-on effects damaging Seattle.

Meanwhile, with Nwosu out, defensive coordinator Clint Hurtt failed to suitably adjust to his new personnel.

When Carroll was asked about an improved run defense following a successful preseason, he enthused to 950 KJR’s ‘Chuck and Buck’ about “the flexibility of it, the ability to pressure and to change looks and make it hard on the good quarterbacks.”

Yet in the latter half of 2023, Seattle was predictable and limited in its front usage and looks, especially on early and neutral downs. Its lack of variety saw adapting offenses stay ahead of the Seahawks.

Macdonald, of course, is a superior coordinator to Hurtt and a tactician renowned for his multiplicity, disguise, and play-call layering. So how did the 2023 Ravens still struggle?

Its illuminating to filter by run type—zone or gap blocking. Baltimore’s ability to stop zone and split zone rushes, as charted by Sports Info Solutions, only slightly worsened in the second half of the season. Meanwhile, opposing attacks utilized these concepts versus the Ravens around the same rate (15.88 attempts a game in first nine compared to 15.22 a game in last eight).

What absolutely gashed Balitmore’s second half of the season run defense was the gap run concepts (pull outside numbers, pull guard, 2+ pullers, backside puller, frontside puller, wham, duo), similar to the AFC championship game.

A big factor in this was the Ravens’ ability to force negative gap run plays vanishing: In the first nine games of the season, the Ravens experienced difficulties but benefited from forcing a 10.6% bust percentage—the percentage of plays that resulted in an EPA below -1—versus gap rushes (fourth-best in the league). In the last eight, Baltimore managed to bust 0.0%! of these gap plays (obviously worst in the NFL).

Opposing offenses took note: the Ravens faced around seven gap runs a game in the second half of the season compared to around five a game in the first.

This wasn’t really a case of Baltimore playing better rushing offenses in the second half: facing an average of 17th in EPA per rush attempt in the last eight; 16th in the first nine. Meanwhile Baltimore’s overall idea on plays basically stayed the same per SIS, be it coverage rates, rush numbers, and blitz percentages, though SIS does identify their usage of stacked box counts actually increasing from 11% to 15% in the second half of the season.

Instead, we must be realistic about the structure of Macdonald’s defense. In the early downs and neutral situations, the Ravens spent most of their snaps in a similar nickel, four-down structure to the Seahawks. Even though Baltimore may have disguised stuff better and been armed with more answers, the inherent weaknesses of the strategy were attacked.

Why gap concepts proved especially difficult is how they can block the wide edge approach and also put extra bodies through the B-Gap bubble, creating dangerous angles and creases in the run game.

As Macdonald himself would say, his run defense weaknesses are now “on tape” for opposing offenses to study. He finds himself in a division with three of the best running offenses in the league last year: Shanahan’s 49ers (fourth in EPA per attempt), McVay’s Rams (sixth), and Gannon’s/Petzing’s Cardinals (first).

Furthermore, these NFC West ground games have started to lean on gap run concepts, with SIS charting the Rams with 93 gap attempts (fifth-most) and the Cardinals with 89 (seventh-most).

Defenses like these nickel over fronts because they accent the two edge defenders, providing reliable four man rush-spacing versus the pass. The solution for stopping the run, though, may be picking and choosing moments to mix in different fronts when in nickel, possible reducing the weak edge into the B gap in an inside shoulder of the tackle, big end type—like Spagnuolo did to success in the Super Bowl—and/or running nickel five down, bear looks.

In Week 10, Browns’ back Jerome Ford had 107 rushing yards versus the Ravens. Then Week 12 saw the Ravens allow Kyren Williams to rush for 114 yards. That led to questions.

“I'm not going to call it a concern, but absolutely an area for improvement,” Macdonald answered back then on the run D.

“It goes with every aspect of the defense, you're always evaluating. We're always thinking through the lens of – ‘Where are we, where do we want to be, and how do we get there?’ That's how we're approaching it.”

Part of why Macdonald has risen so rapidly is his ability to successfully adapt to situations. This reputation brings expectation that would add extra disappointment if Seattle produces a third successive year of shoddy run defense. Watching how the head coach creates further answers for this run challenge is a fascinating part to 2024 Seahawks defense.

This article was edited by Alistair Corp, my former Field Gulls editor.

Thank you for being a paid subscriber to Seahawks On Tape, I greatly appreciate it. Please enjoy these highly relevant Mike Macdonald resources in the link below. And please also comment what you’d like to see next at SOT.

Matty